You often hear people talking about learning as if it is something you do in school, or while reading a book, or while the drill sergeant is looking at you, but not otherwise. You hear utterances like, "She just won't learn!" or "He is a slow learner." Well, he may be slow about learning the things you want him to learn, but his neural pulses travel just as fast as anybody elses. (p. 241)

The Life, Times, and Work of Alfred Korzybski with Non-Aristotelian Sightings and Comments on the Passing Scene

Friday, December 26, 2008

Runkel On Learning

I knew at least peripherally the late Philip J. Runkel, a great but not necessarily well-known social psychologist. Phil and I had corresponded because I was interested in Perceptual Control Theory (PCT)—he was one of the major figures in that 'school' of psychology—and Phil had also studied and respected Korzybski's work. I often dip into Phil's last book now, People As Living Things: The Psychology of Perceptual Control for a measure of both theoretical and practical wisdom. Here's a little quote on learning from that book:

Sunday, December 21, 2008

Null-A Continuum

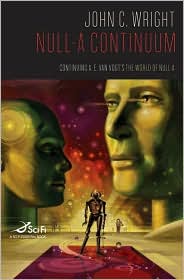

On jury duty last week, I didn't manage to get out a blog post—not an excuse, but I hope at least for my readers' sympathetic understanding. It took four days with a lot of waiting to finally find out that I wasn't going to get picked to serve as a juror in a murder trial. The jury selection process fascinated me nonetheless and I actually felt a little disappointed when the D.A. knocked me off of the panel. Beside that, the waiting time gave me a chance to catch up on my reading. One of the books I finished was John C. Wright's Null-A Continuum.

I met John C. Wright last month at the 2008 Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture weekend in New York City sponsored by the Institute of General Semantics. He drove up from Virginia, to speak on the last day of the conference about his book, based on the 'Null-A' world created by A.E. Van Vogt. Having read all three of Van Vogt's Null-A books years ago, I bought a copy of Wright's book, made sure that Wright signed it, and had a few pleasant minutes of conversation with him. I was amused when his young son, about 8 or 9 I guess, tried to get his father's attention while we were talking and Wright asked him to stop and take a "cortico-thalamic pause." More children should know how to do that!

The Null-A books, started as a series in Astounding science fiction magazine in the mid-1940s. Van Vogt's book The World of Null-A based on these stories came out in the late 1940s. It has continued to be in print in numerous editions (along with two sequels) since then. I read the Null-A books sometime in the 1960s or early 1970s. I was already a student of Korzybski's work and the books, with their 'weird' story of Gilbert Gosseyn, the Games Machine, the Semantic Institute on Korzybski Square, and a libertarian 'Null-A' society on Venus, had a compelling quality although I found the plot confusing. (Korzybski did too. He read the Astounding stories and when the book came out read that as well, three times in fact and still confessed confusion about what it was about. Korzybski wasn't actually very much of a science fiction reader.) The books stimulated a significant number of readers to learn more when they realized that Van Vogt based the non-aristotelian teachings of the book and the sayings that began each chapter on the work of an actual person named Korzybski. Though the books were my introduction to Van Vogt's writing, they are not my favorites among Van Vogt's writings. (I have since come to love much more The Voyage of the Space Beagle and some of his short stories (see The Best of A.E. Van Vogt).

The Null-A books were definitely a major influence and favorite of Wright, who as a young science fiction fan in the 1970s 'ate up' the stories which deeply resonated with something in him and provided a major inspiration for his eventual career as a science fiction writer. He got the permission of Van Vogt's widow to write a continuation of the series. And remarkably, he has managed somehow to capture Van Vogt's 'spirit' and voice in this book. For me, the book dragged a little toward the middle, which may have had something to do with the convoluted (to me) Van Vogt plot-line that Wright sought to continue. But Wright is a talented enough writer to have succeeded in grabbing my attention when I felt my interest lag (much as Van Vogt had the power to do) and I enjoyed the book. If you liked the Null-A books I think you will like this one, indeed you MUST get it since it gives a satisfying ending to the saga of Gilbert Gosseyn—one that Van Vogt could be proud of.

Interestingly, other than whatever he got from Van Vogt's books, Wright hasn't read Korzybski's work or any other G.S. literature (as far as I know). But he definitely has a feel for it, beginning each chapter with one of a number of apt 'Null-A' mottos that he has formulated, e.g., "The Laws of Men will never be just until they are sane," "Fear is the reaction of the living organism, not to threat, but to the perception of threat," "Analyzing the universe into simple binary opposites, while necessary, has limited value," et cetera. Null-A Continuum may even get some of its readers to seek to find out more about Korzybski and general semantics, just like Van Vogt's novels did.

Thumbs up to John C. Wright!

Links

Wikipedia biography of John C. Wright (caveat lector!)

John C. Wright's Web Log

Null-A Continuum on Amazon.com

A comprehensive website on A.E. Van Vogt and his Work

Thursday, December 11, 2008

Nothing To Fear But...

An amusing (to me) YouTube video, a comedy sketch from Israeli television, illustrates the multiordinal quality of human reactions, in this case phobias.

Multiordinality, in the korzybskian sense, stems from the self-reflexive capacity of the nervous system that allows us to react to our reactions.

The multiordinality of terms, reflects this capacity and refers to the fact that such terms have different 'meanings' depending on the level of abstraction on which they are used. Such terms can be applied to themselves at different levels of abstraction.

For example, I can be in love. I can also be in love with being in love. I can hate someone or something. I can hate hate. And I can fear something as well as come to fear my fear. One can feel anxiety and also anxiety about anxiety. We react not only to our own reactions but to others reactions as well. Understanding the mechanism and being able to laugh at it can make a difference, I think, as the video shows.

Multiordinality, in the korzybskian sense, stems from the self-reflexive capacity of the nervous system that allows us to react to our reactions.

The multiordinality of terms, reflects this capacity and refers to the fact that such terms have different 'meanings' depending on the level of abstraction on which they are used. Such terms can be applied to themselves at different levels of abstraction.

For example, I can be in love. I can also be in love with being in love. I can hate someone or something. I can hate hate. And I can fear something as well as come to fear my fear. One can feel anxiety and also anxiety about anxiety. We react not only to our own reactions but to others reactions as well. Understanding the mechanism and being able to laugh at it can make a difference, I think, as the video shows.

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

Winning The War On Nerves: Becoming Aware Of Pathological Verbal Distortion

Korzybski, in his "Introduction to the Second Edition" of Science and Sanity wrote at great length about the general semantic (evaluational) aspect of the war against Nazi Totalitarianism. The Nazis, as he pointed out, spent much time and money in the service of propaganda for their cause. "Pathological verbal distortion" as Korzybski called it, provided a major tool in what he called their "war of and on nerves" against the Allies. He wanted the Allies—America had not yet entered the war when he was writing this in 1940 and early 1941—to pay serious attention to this and hoped that the U.S. government would realize that it needed to make use of professional psychiatric, psycho-logical experts as well as the neuro-semantic (evaluational), neuro-linguistic training that he was offering, in order to deal with the Nazi threat adequately.

I'd like to call the reader's attention to a little of what Korzybski wrote:

Steve Emerson writes eloquently about this in his article, "Yes the terrorists are winning. He condemns the 'contrived evenhandedness' which he noted in coverage of the Mumbai massacre by mainstream media outlets like the New York Times. He writes:

I'd like to call the reader's attention to a little of what Korzybski wrote:

There are persistent reports that the Nazi government is utilizing a staff of psycho-logical experts for destructive purposes. Other totalitarian governments ape their successfully worked out and tested methods. The 'democratic' governments in this present fundamental nerve contest appear a tragic joke of ignorance, inefficiency, etc.In practice this amounts to betrayal, because they fail to recognize the overwhelming importance and vulnerability of the human nervous system, and do not utilize such experts in a constructive way. (p. lxxi, in S&S, 5th ed.)On the next page he wrote:

The violation, through ignorance and/or un-sanity of the similarity of structure in the map-territory relationship (see p. 58 ff. and p.750 ff), and/or deliberate, professionally planned distortion of it, abolishes predictability, proper evaluation, trust, etc. This results only in breeding fears, anxieties, hates, etc., which disorganize individuals and even nations. There must be a correspondence and similarity of structure between language and facts, and so consequent thalamo-cortical integration, if we are to survive as a sane 'civilized' race. (p. lxxii)Well folks, It appears we are now in another war of and on nerves. What Korzybski wrote about the free world's response to Naziism seems relevant today. We are now, in my opinion (but not just my opinion), in a war with Islamism (Totalitarian Islam) and our governments and media, to a significant extent, have already succumbed to—and indeed now help to promote—the pathological verbal distortions that those who have declared jihad against us want us to accept.

Steve Emerson writes eloquently about this in his article, "Yes the terrorists are winning. He condemns the 'contrived evenhandedness' which he noted in coverage of the Mumbai massacre by mainstream media outlets like the New York Times. He writes:

Watching and reading reports of the Mumbai attacks was an Alice in Wonderland experience. Even after an Islamic terrorist group took credit, TV anchors and reporters assiduously avoided the term Islamic terrorist. They must have consulted with the Thesaurus for the Politically Correct to determine that the word "gunmen" would not offend any jihadist.To those readers who may feel offended by what they may consider a 'politically-incorrect' blogpost, I suggest (as I do for everyone else too) that they read Emerson's entire article—perhaps more than once—before sending 'nasty' comments and emails to me. This blog is about Korzybski and his work. If you are going to practice 'general semantics' and not just talk about it, you've got to face 'facts' whether you find them pleasant or not. We are still very far from the non-aristotelian reorientation of human civilization that Korzybski envisioned. We won't get any closer to it by ignoring the very big 'fact' of the Islamist War against the West, the Jews and Modernity.

The real truth is that there is war against the West and the Jews by Islamic jihadists.

On Wednesday, even though everyone knew by then that the perpetrators were jihadists, CNN constantly referred to the terrorists as "extremists"-with no modifier. Hell, they could have been the Basque ETA or the ultra right wing U.S. militia. Then a CNN anchor asked his guest with totally innocence, "Now why would an extremist group target a Jewish house of worship?" Because, my dear politically correct anchor, it was an Islamist terrorist group. ...

....It all comes together. After more than 7 years since 9/11, we can now issue a verdict: Islamic terrorists have won our hearts and minds. Let's thank those who made it happen: the U.S. government, European governments and the mainstream media. It's time to stop placating or being intimidated by Islamic front groups who masquerade as civil rights groups. In 2007, the perversity of [this] was demonstrated when the FBI released its annual 2007 hate crime reports. Of the total 1,628 victims of anti-religious hate crimes, 69.2% were Jewish and 8.7% were Muslim. Yet by my still unfinished account, there were at least 40 times more stories last year about Islamophobia than about anti-Semitism.

The Mumbai massacre was a heavily planned plot carried out by Islamic terrorists. Period. Memo to Obama: Until the onus of responsibility is put on Islamic "civil rights" groups that want to ban free speech and claim that anyone who uses the term Islamic terrorist is a racist, there is no hope of winning the battle.

Friday, November 28, 2008

G.S. in Six Words

There's a book whose title explains what's in it: Not Quite What I Was Planning: Six-Word Memoirs by Writers Famous and Obscure.

I thought I'd give this six-word treatment a try to describe Korzybski's work:

I found an interesting blogpost here by 'The Climateer' on the current financial mess we are in: After The Crash: How Software Models Doomed The Market The writer references Korzybski. Click on the link to the post where he discusses G.S. [General Semantics] in more detail here: Modeling:The Map Is Not The Territory. Nassim Taleb has made similar points (quoting Korzybski—without attribution) about the folly of economists taking their models too seriously.

Map not territory, simple—not easy!

I thought I'd give this six-word treatment a try to describe Korzybski's work:

"Map not territory, simple—not easy."As Gregory Bateson pointed out, every schoolboy 'knows' that a map is not the territory it represents, doesn't represent all of the territory, etc. Yet application of this understanding remains rather more difficult than many people imagine. The news is full of stories illustrating map-territory, model-actuality, word-thing, etc., confusions.

I found an interesting blogpost here by 'The Climateer' on the current financial mess we are in: After The Crash: How Software Models Doomed The Market The writer references Korzybski. Click on the link to the post where he discusses G.S. [General Semantics] in more detail here: Modeling:The Map Is Not The Territory. Nassim Taleb has made similar points (quoting Korzybski—without attribution) about the folly of economists taking their models too seriously.

Map not territory, simple—not easy!

Thursday, November 20, 2008

Dr. Jay Katz – Z"L

Reading today's obituary page of The New York Times (which we have delivered every morning out here in Pasadena), I saw that Jay Katz died on Monday. As I read the obit, I didn't realize at first that they were referring to the Jay Katz whose book I had read some time ago and so much appreciated.

I have devoted this blog to Korzybski, his work, and related matters. The work of Jay Katz, a humane and extensional physician, definitely qualifies as one of those related matters. I read his book 'The Silent World of Doctor and Patient' years ago, have it on my book shelf, and recommend it to everyone interested in general semantics and clear, sane evaluating in relation to medical issues.

As a young German Jew, he escaped from Nazi Germany just before World War II. After he became a physician, he eventually focused on psychiatry and medical ethics. He was a working doctor and a working ethicist and he knew what he was talking about, i.e., he didn't indulge in idle, detached 'philosophical' chatter but engaged the most serious issues of medicine and life with the most serious of concerns. He was one of the physicians appointed to the federal panel to investigate the 1932 Tuskeegee Syphilis Study, done by the U.S. Public Health Service. When the panel's report came out describing the Tuskeegee experiments as "ethically unjustified," that wasn't good enough for Jay Katz. (The Tuskeegee researchers had purposely withheld treatment to 400 black men infected with syphilis.) Katz issued his own statement saying that the infected men had been "exploited, manipulated, and deceived." Jay Katz had 'guts'.

He believed that people's capacity for autonomy and self-determination were not unlimited but that physicians and researchers ought to do what they could to respect that capacity and encourage it. And they could do so through the medium of their conversations with their patients. If that isn't a worthy topic for general-semantics students to explore, I don't know what is.

Read the obituary Dr. Jay Katz, 86, Dies; Explorer of Ethics Issues. Read his book The Silent World of Doctor and Patient

I have devoted this blog to Korzybski, his work, and related matters. The work of Jay Katz, a humane and extensional physician, definitely qualifies as one of those related matters. I read his book 'The Silent World of Doctor and Patient' years ago, have it on my book shelf, and recommend it to everyone interested in general semantics and clear, sane evaluating in relation to medical issues.

As a young German Jew, he escaped from Nazi Germany just before World War II. After he became a physician, he eventually focused on psychiatry and medical ethics. He was a working doctor and a working ethicist and he knew what he was talking about, i.e., he didn't indulge in idle, detached 'philosophical' chatter but engaged the most serious issues of medicine and life with the most serious of concerns. He was one of the physicians appointed to the federal panel to investigate the 1932 Tuskeegee Syphilis Study, done by the U.S. Public Health Service. When the panel's report came out describing the Tuskeegee experiments as "ethically unjustified," that wasn't good enough for Jay Katz. (The Tuskeegee researchers had purposely withheld treatment to 400 black men infected with syphilis.) Katz issued his own statement saying that the infected men had been "exploited, manipulated, and deceived." Jay Katz had 'guts'.

He believed that people's capacity for autonomy and self-determination were not unlimited but that physicians and researchers ought to do what they could to respect that capacity and encourage it. And they could do so through the medium of their conversations with their patients. If that isn't a worthy topic for general-semantics students to explore, I don't know what is.

Read the obituary Dr. Jay Katz, 86, Dies; Explorer of Ethics Issues. Read his book The Silent World of Doctor and Patient

Post-IGS Symposium Quick Update

I got back home from New York City on Tuesday. Exhausted. Full of hope and new ideas. My research at the Korzybski archives at Columbia University went very well. Douglas Rushkoff gave a very interesting Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture. The weekend symposium that followed, at Fordham University-Lincoln Center, sponsored by the Institute of General Semantics, exceeded my expectations. Some fantastic speakers presented (you can still download the well-worth-a-look program). I saw many old friends and made a number of new ones. With Lance Strate, Bill Petkanas and others now involved the Institute is in very good hands.

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

2008 Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture and Symposium

On Thursday I'm off to New York City to participate in the Weekend Symposium following the Friday Evening Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture given by Douglas Rushkoff. Rushkoff's lecture entitled Playing the Future: Towards a Creative Society. follows a sumptuous—I hope—dinner at the Princeton Club. I'm looking forward to it. I expect to see some old friends that I haven't seen in awhile—and meet some new ones.

I'll also use the trip to do some research at Columbia University's Butler Library Rare Book & Archives Collection, which holds materials related to both Alfred Korzybski and his wife Mira Edgerly Korzybska.

The symposium, entitled Creating the Future: Conscious Time-Binding for a Better Tomorrow, promises a fascinatingly full two days on Saturday and Sunday, with a number of interesting speakers including (I humbly assert) myself. I'll be giving a presentation on Saturday at 12:30 just before lunch on "What Did Alfred Want? A Biographer's Notes on Korzybski's Life and Work." The symposium is free so if you're in the area of the McNally Auditorium at Fordham University, Lincoln Center in Manhattan, I'll be delighted to see you. The Saturday morning festivities start at 9 a.m.

Lance Strate, Executive Director of the Institute of General Semantics, has posted a program for the weekend on his blog (Link under Blog listings on Right). I'm sure I'll have at least a few things to say about the weekend's events after I get back next Tuesday. Until then, I apologize for the spareness of this week's blog. I've been somewhat busy preparing.

In the meantime, I'll leave you with a statement from Alexis Carrel which Korzybski was fond of quoting at the end of his seminars (along with some quotes from others). The theme of the AKML weekend is related to creativity and I think Carrel indicated something that creativity sometimes requires:

I'll also use the trip to do some research at Columbia University's Butler Library Rare Book & Archives Collection, which holds materials related to both Alfred Korzybski and his wife Mira Edgerly Korzybska.

The symposium, entitled Creating the Future: Conscious Time-Binding for a Better Tomorrow, promises a fascinatingly full two days on Saturday and Sunday, with a number of interesting speakers including (I humbly assert) myself. I'll be giving a presentation on Saturday at 12:30 just before lunch on "What Did Alfred Want? A Biographer's Notes on Korzybski's Life and Work." The symposium is free so if you're in the area of the McNally Auditorium at Fordham University, Lincoln Center in Manhattan, I'll be delighted to see you. The Saturday morning festivities start at 9 a.m.

Lance Strate, Executive Director of the Institute of General Semantics, has posted a program for the weekend on his blog (Link under Blog listings on Right). I'm sure I'll have at least a few things to say about the weekend's events after I get back next Tuesday. Until then, I apologize for the spareness of this week's blog. I've been somewhat busy preparing.

In the meantime, I'll leave you with a statement from Alexis Carrel which Korzybski was fond of quoting at the end of his seminars (along with some quotes from others). The theme of the AKML weekend is related to creativity and I think Carrel indicated something that creativity sometimes requires:

To progress again, man must remake himself. And he cannot remake himself without suffering. For he is both the marble and the sculptor.

Wednesday, November 5, 2008

Airport Security And Other Predictably Irrational Things

Dan Ariely studies human evaluative behavior-decisionmaking. Basically, that's what Korzybski focused on as well.

Ariely calls what he does 'behavioral economics'. You can understand the core of Korzybski's work—called 'general semantics'— a lot better by seeing its closeness to behavioral economics, for example, than by viewing it as some kind of 'philosophy' of 'language'. If you do the latter, you probably put a terribly unfortunate limit on your ability to perceive the scope of Korzybski's work.

But one of the many ways that people get misled (alot of what Ariely studies) is by how they interpret words, in their own 'habitual' fashion which may not have much to do with the writer's/speaker's (in this case Korzybski's) intentions. Thus, when many people see or hear the word 'semantics' in 'general semantics', they interpret this as having to do with the 'meanings' of words and/or language. Korzybski emphasized (more and more frequently as time went on) that 'general semantics' referred to a general theory of evaluation. 'Semantic' reactions, 'semantic' environments, 'semantic' factors, as he said many times, equated with evaluation, evaluational reactions, evaluational environments, and evaluational factors. Evaluation as he discussed it covered 'thinking' and 'feeling', on verbal and non-verbal levels. His study in evaluation, human values, human behavior extended beyond concerns about 'language', although surely the study of 'language structure' and language-related behavior had an important role to play in his work.

If any of you students of 'general semantics' out there find this confusing—Good! The following Youtube video is for you. Ariely's amusing behavioral economics piece on optical 'illusions', human perception, decision-making, mis-evaluation could serve just as well as an excellent GS teaching-demonstration.

Now if you wondered when I would ever get to the topic of airport security—here it is. Ariely shows how some of the people of the T.S.A. (the U.S. Transportation Safety Administration) at our airports are working to keep us 'safe' when we fly. I feel so relieved. Enjoy!

Ariely calls what he does 'behavioral economics'. You can understand the core of Korzybski's work—called 'general semantics'— a lot better by seeing its closeness to behavioral economics, for example, than by viewing it as some kind of 'philosophy' of 'language'. If you do the latter, you probably put a terribly unfortunate limit on your ability to perceive the scope of Korzybski's work.

But one of the many ways that people get misled (alot of what Ariely studies) is by how they interpret words, in their own 'habitual' fashion which may not have much to do with the writer's/speaker's (in this case Korzybski's) intentions. Thus, when many people see or hear the word 'semantics' in 'general semantics', they interpret this as having to do with the 'meanings' of words and/or language. Korzybski emphasized (more and more frequently as time went on) that 'general semantics' referred to a general theory of evaluation. 'Semantic' reactions, 'semantic' environments, 'semantic' factors, as he said many times, equated with evaluation, evaluational reactions, evaluational environments, and evaluational factors. Evaluation as he discussed it covered 'thinking' and 'feeling', on verbal and non-verbal levels. His study in evaluation, human values, human behavior extended beyond concerns about 'language', although surely the study of 'language structure' and language-related behavior had an important role to play in his work.

If any of you students of 'general semantics' out there find this confusing—Good! The following Youtube video is for you. Ariely's amusing behavioral economics piece on optical 'illusions', human perception, decision-making, mis-evaluation could serve just as well as an excellent GS teaching-demonstration.

Now if you wondered when I would ever get to the topic of airport security—here it is. Ariely shows how some of the people of the T.S.A. (the U.S. Transportation Safety Administration) at our airports are working to keep us 'safe' when we fly. I feel so relieved. Enjoy!

Sunday, October 26, 2008

Homer J. Moore, Jr., Korzybskian Scholar and Beloved Friend — Z"L.

My dear friend Homer Jean Moore, Jr. died at his home in Texas on October 22. His family and loved ones were with him. (The Z"L abbreviation in the Title above stands for Zichrono L'vracha, Hebrew for "May his memory be a blessing" or "Of Blessed Memory." This is often placed or said after the name of a deceased Jewish person. Homer Jean wasn't Jewish. Nonetheless, "Zichrono L'vracha" seems appropriate for him. He attended a lot of Passover Seders. He liked Jews and Jewish things. As a Jew and his friend, I do consider his memory a special blessing.)

My dear friend Homer Jean Moore, Jr. died at his home in Texas on October 22. His family and loved ones were with him. (The Z"L abbreviation in the Title above stands for Zichrono L'vracha, Hebrew for "May his memory be a blessing" or "Of Blessed Memory." This is often placed or said after the name of a deceased Jewish person. Homer Jean wasn't Jewish. Nonetheless, "Zichrono L'vracha" seems appropriate for him. He attended a lot of Passover Seders. He liked Jews and Jewish things. As a Jew and his friend, I do consider his memory a special blessing.) A long time student-practitioner of general semantics, be attended his first Institute of General Semantics (IGS) seminar-workshop (2 weeks long) in 1979, although he had been a long-time student of Korzybski's work before then. He soon became one of the small number of workers who helped keep the Institute going over the next few decades. He also served for a number of years on the IGS Board of Trustees.

Homer was one of few people who went through the rigorous teacher training course that the Institute had in place through 1980s and 1990s, became certified to teach, and served on the Institute teaching staff at a number of Institute advanced and beginner's training courses with myself and my wife.

In the miniscule non-academic field of general semantics and Korzybskian studies, Homer—originally trained in computer programming and systems analysis—was one the discipline's few genuine scholars. His editorial contributions included some writing, much work on the IGS internet site, and various publications, including the editing and much of the production, of the Third Edition of Korzybski's General Semantics Seminar 1937: The Olivet College Lectures, published in 2002. Homer's new Third Edition became the first one in which this book actually appeared as a book and not a roughly printed booklet with cheap galley covers. It became a genuine advance in promulgating Korzybski's work. Homer's Third Edition may qualify as the single best introduction to Korzybski's work in Korzybski's down-to-earth oral presentation style. In his Foreword, Homer wrote:

In this early presentation, [Korzybski] gives a complete outline of his system with the training methods needed to apply it. This seminar makes an excellent starting point for those wishing to apply general semantics in their daily lives.Homer exemplified such application (Korzybski's main emphasis).

I plan on writing more about Homer here and elsewhere. He was one of the most exceptional practitioners of GS that I have ever known. He was born in 1951 with serious heart valve problems and was one of the first babies operated on by famed heart surgeons Denton Cooley and Michael DeBakey. They saved his life but he also received numerous blood transfusions in his early years, which he discovered much later must have been contaminated with the Hepatitis C virus. He struggled with various vague health problems most of his life before he was diagnosed with the disease and liver failure in the early 1990s. Eventually, with his liver function deteriorating, he managed to obtain a liver transplant about 10 years ago. This year he had been struggling with continuing health problems and his new liver finally failed, although his sister Linda told me that he had a fairly quick exit. (I had just talked with him a month or two ago and he seemed fairly well—given everything he was dealing with.) Living with serious health problems most of his life, he had an ability to adjust and deal with things that few people will ever have to deal with. A roller coaster 'fanatic' and prodigious reader (among other avocations and vocations) he sought to live life to the fullest— a curious and awe-inspired participant-observer in a world that he considered wonder-full, even 'miraculous'. His own consciousness constituted one of the most wondrous and awesome parts of the world for Homer. Korzybski's "coveted consciousness of abstracting" was not just words to him. He worked at it. And he attained a fine character, perhaps the most precious thing that any man or woman can achieve. Homer's exceptional coping skills were reflected in his special dry and seemingly ever-present sense of humor (not in telling jokes but in his attitude toward life) and in his unstinting kindess and generosity to others. Oh yes—he applied GS.

Homer contributed in inumerable ways to the Institute of General Semantics, in work, wealth and wisdom and the furtherance of Korzybski's work for human sanity. My wife and I are among those who will sorely miss him.

Saturday, October 18, 2008

Time-Binding - So What? Part V

J. seems to have gotten more interested in time-binding, although he still has some formulational problems with it. (Read the comment on the previous post). So I feel that I've done some good with this "So What?" series of blogposts. For now, I'll let his continuing theoretical concerns 'simmer' and move on to practical applications. If you consider yourself a time-binder, so what? In that last post, I ended with some questions to ponder, to get a living feel for the implications of time-binding to you. I want to add here another question that can make it more 'real' for you.

My wife Susan Presby Kodish came up with a time-binding question that we use in personal coaching work and classes: What do you want your legacy to be?

You won't live forever. Usually we think of a legacy as an amount of money or property left for an inheritance. Here I mean something different, although it could include these kinds of things. Rather by legacy I mean something related to how you would like to be remembered after you're gone. This doesn't have to be by way of some great masterpiece you leave that everyone recognizes or a monument erected in your memory. Rather by legacy, I mean more precisely: what difference you would like your presence to have made on others, on the world (whether or not recognized). Don't think that because your name may be forgotten in a few hundred years—likely sooner—that your existence in the world now doesn't make a difference.

Professor J.T. Shotwell wrote about two kinds of immortality:

(1). Qtd. in Ashley Montagu 1955, Immortality. New York: Grove Press, p. 66. From James T. Shotwell 1942, "Mechanism and Culture." In Science and Man, Ed. By R. N. Anshen. New York: Harcourt Brace & Co.

My wife Susan Presby Kodish came up with a time-binding question that we use in personal coaching work and classes: What do you want your legacy to be?

You won't live forever. Usually we think of a legacy as an amount of money or property left for an inheritance. Here I mean something different, although it could include these kinds of things. Rather by legacy I mean something related to how you would like to be remembered after you're gone. This doesn't have to be by way of some great masterpiece you leave that everyone recognizes or a monument erected in your memory. Rather by legacy, I mean more precisely: what difference you would like your presence to have made on others, on the world (whether or not recognized). Don't think that because your name may be forgotten in a few hundred years—likely sooner—that your existence in the world now doesn't make a difference.

Professor J.T. Shotwell wrote about two kinds of immortality:

...the immortality of monuments,—of things to look at and recall; and the immortality of use,—of things which surrender their identity but continue to live, things forgotten but treasured, and incorporated in the vital forces of society. Thought can achieve both kinds. It embodies itself in forms—like epics, cathedrals and even engines—where endurance depends upon the nature of the stuff used, the perfection of the workmanship and the fortune of time. But it also embodies itself in use; that is, it can continue its work, enter into other thought and continue to emit its energy even when its original mold is broken up. (1)As a time-binder, you will leave a legacy, willy-nilly, whether you do it purposefully or not. What do you want yours to be?

(1). Qtd. in Ashley Montagu 1955, Immortality. New York: Grove Press, p. 66. From James T. Shotwell 1942, "Mechanism and Culture." In Science and Man, Ed. By R. N. Anshen. New York: Harcourt Brace & Co.

Monday, October 13, 2008

Time-Binding - So What? Part IV

J., a reader of this blog, indicated that he wasn't very interested in the notion of "time-binding." I've used the previous posts with the above title to address his implied question "So what?" Why should time-binding concern him?

I hope I've given him (and others) some things to chew on. Time-binding, for one thing, got Korzybski started. Trying to figure it out led him to develop his subsequent work.

Aside from its relevance to understand what Korzybski was doing, what (as J. asked) "authorizes this particular description over all the other potential descriptions of 'what dominantly characterizes humans'?"

Korzybski felt (and I agree) that this capacity to build upon what others have done—based upon our uniquely symbolic brains—does most characterize humans. If that at least seems plausible then we can proceed to see what develops from it. Fruitfulness 'is all'. What develops from starting to think of yourself as a time-binder? Let's extensionalize this, bring it down to earth.

As an exercise, I suggest contemplating one or more of these time-binding questions:

I hope I've given him (and others) some things to chew on. Time-binding, for one thing, got Korzybski started. Trying to figure it out led him to develop his subsequent work.

Aside from its relevance to understand what Korzybski was doing, what (as J. asked) "authorizes this particular description over all the other potential descriptions of 'what dominantly characterizes humans'?"

Korzybski felt (and I agree) that this capacity to build upon what others have done—based upon our uniquely symbolic brains—does most characterize humans. If that at least seems plausible then we can proceed to see what develops from it. Fruitfulness 'is all'. What develops from starting to think of yourself as a time-binder? Let's extensionalize this, bring it down to earth.

As an exercise, I suggest contemplating one or more of these time-binding questions:

* Can you find anything that you have made, arranged, organized, composed, written, etc., that didn't in some way depend upon the contributions of others?These questions can help you get a feel for yourself as a time-binder. What kind of difference could becoming more consciously aware of yourself as a time-binder make in your life?

* Take an object from your pocket, desktop, or around your house or office. How did it get here? How was it manufactured? Trace things back a bit. How many people were involved in making it and getting it to the store or place where you bought it or got it from? Who invented it? What other inventions were required to produce it? Et cetera.

* How did you come to be reading this weblog?

Wednesday, October 8, 2008

Some Strate Talk About Time-Binding

My friend Lance Strate, Executive Director of the Institute of General Semantics has begun to blog about time-binding.

I consider his meditations definitely worth reading and especially like what he wrote at the end of his second piece "Thoughts About Time-Binding 2"

Check out "Thoughts About Time-Binding 2" and also Lance's first post"Thoughts About Time-Binding 1"

I consider his meditations definitely worth reading and especially like what he wrote at the end of his second piece "Thoughts About Time-Binding 2"

So, even if you don't care for Korzybski and general semantics, or don't agree with the conclusions arrived at, there is much to be gained from going back to the original questions that Korzybski posed, seeing how he answered them, and answering them again for ourselves, in the context of our own time. This is a worthwhile exercise as well for those who are completely in agreement with Korzybski. To make an analogy with mathematics, it is not enough to get the right answers, you have to go through the process by which they were attained, understand that process, and make it your own.Lance practices what he preaches. If you do what he beautifully demonstrates, i.e., go back to the original material—Korzybski's own writing—(not what Bruce or Lance says about it ) and contend with the questions he raises, you will reap rewards that you wouldn't otherwise get.

Check out "Thoughts About Time-Binding 2" and also Lance's first post"Thoughts About Time-Binding 1"

Tuesday, October 7, 2008

Time-Binding - So What? Part III

The very astute J. has pointed to something notable about Korzybski's formulation of time-binding. Time-binding, as Korzybski formulated it, is not simply descriptive or ethically neutral. As J. wrote:

Of course, this value-laden aspect of time-binding seems to open up a formulational 'can of worms'. Judging the relative time-binding merits of different human acts and products doesn't seem necessarily clearcut. How do we operationalize time-binding and 'progress' so we can observe and measure them? I've dealt with this question at more length in my book Dare to Inquire Despite whatever problems the formulation may pose, all (legitimately all) of Korzybski’s subsequent work, which came to be called “general semantics,” involved his efforts to investigate and explain the mechanisms of time-binding. If you are interested in understanding Korzybski's work and how it developed, that alone justifies giving attention to time-binding.

As for J's subsidiary question

Time binding seems like a description transformed into prescription (?); e.g. "Dog's often bark, therefore, dogs should bark 'better'. Where's the logic in this?Korzybski's formulation definitely was not simply limited to a description of the unique human ability to communicate via symbolism. He very clearly defined time-binding in terms of a capacity, a potential that the human ability to communicate makes possible: the capacity to begin where another individual or generation left off and thus be able to build on previous efforts in order to make ‘progress’. Stated in terms of human potential, his formulation of time-binding implies an 'ought', a value-laden criterion, as well as an 'is', a description of what people do. Korzybski wanted people to become better time-binders.

Of course, this value-laden aspect of time-binding seems to open up a formulational 'can of worms'. Judging the relative time-binding merits of different human acts and products doesn't seem necessarily clearcut. How do we operationalize time-binding and 'progress' so we can observe and measure them? I've dealt with this question at more length in my book Dare to Inquire Despite whatever problems the formulation may pose, all (legitimately all) of Korzybski’s subsequent work, which came to be called “general semantics,” involved his efforts to investigate and explain the mechanisms of time-binding. If you are interested in understanding Korzybski's work and how it developed, that alone justifies giving attention to time-binding.

As for J's subsidiary question

Why is this transformation relevant, and what authorizes this particular description over all the other potential descriptions of 'what dominantly characterizes humans'?I'll leave that for another post.

Thursday, October 2, 2008

Time-Binding - So What? Part II

My reader J has said "I'm not very interested in time-binding..." He must have a lot of patience since I have given over a great deal of this blog space so far to discussing time-binding. I'm asking J and others who may feel similarly to have even a bit more patience with me.

Having now spent more than four years working on a biography of Korzybski (getting near completion now), I have felt obligated to deal with time-binding in some depth and detail, since (in his own eyes) it played such an important role in the development of his work. He devoted his first book, Manhood of Humanity, to the notion. And, as he said on numerous occasions, all of his subsequent work—which he subsequently called "general semantics" developed out of his efforts to clarify and elaborate the mechanism of time-binding, i.e., how time-binding worked.

He didn't talk or write much explicitly about time-binding after the 1933 publication of Science and Sanity, until the last few years of his life when he returned to the subject with renewed vigor. He had been working for some time on a new introduction to the Second Edition of Manhood but was unable to complete it before his death in March 1950.

Korzybski was very interested in time-binding. I have come to agree with Korzybski as to its importance. Because of this, I have felt compelled to spend a fair amount of time dealing with time-binding in my book and, as a result, in this blog.

But this only begins to touch on the question "So what?"

Having now spent more than four years working on a biography of Korzybski (getting near completion now), I have felt obligated to deal with time-binding in some depth and detail, since (in his own eyes) it played such an important role in the development of his work. He devoted his first book, Manhood of Humanity, to the notion. And, as he said on numerous occasions, all of his subsequent work—which he subsequently called "general semantics" developed out of his efforts to clarify and elaborate the mechanism of time-binding, i.e., how time-binding worked.

He didn't talk or write much explicitly about time-binding after the 1933 publication of Science and Sanity, until the last few years of his life when he returned to the subject with renewed vigor. He had been working for some time on a new introduction to the Second Edition of Manhood but was unable to complete it before his death in March 1950.

Korzybski was very interested in time-binding. I have come to agree with Korzybski as to its importance. Because of this, I have felt compelled to spend a fair amount of time dealing with time-binding in my book and, as a result, in this blog.

But this only begins to touch on the question "So what?"

Friday, September 26, 2008

Time-Binding - So What? Part I

A reader of this weblog (I'll call him J) wrote

Since I like to make my blogposts shorter rather than longer, I'm going to take more than one blogpost to unpack this. Here goes.

Let me start with a rough and ready set of statements about time-binding from the glossary of Drive Yourself Sane.

I'm not very interested in time-binding...Time binding seems like a description transformed into prescription (?); e.g. "Dog's often bark, therefore, dogs should bark 'better'. Where's the logic in this? [i.e. Why is this transformation relevant, and what authorizes this particular description over all the other potential descriptions of 'what dominantly characterizes humans'He also said that he was interested in "applications to 'our' everyday life." He seemed to have some difficulty seeing how time-binding and perhaps other formulations/principles of general semantics could be used "for assessing our personal goals, dreams, and/or purposes in life."

Since I like to make my blogposts shorter rather than longer, I'm going to take more than one blogpost to unpack this. Here goes.

Let me start with a rough and ready set of statements about time-binding from the glossary of Drive Yourself Sane.

Time-Binding: the characteristic human ability, using language and other symbols, to transmit information across time; the potential for individuals to learn from their own and other people's experiences; the potential for each generation to start where the last generation left off, the potential to become aware of this ability; this allows for the formation of cultures and the ability to study cultures, etc.Starting from this, I'll try to address J's puzzlement.

Monday, September 22, 2008

Follow The Korzybski Files

I know that I'm not the only person who reads this weblog. 8-) I occasionally get an email from readers beside the comments that people post here (so far all too infrequently). So I know that I'm not not just talking to myself. There are alot of people interested in Korzybski, what he did and wrote, and what the work he started implies for us today (2008). I'd like to hear from you. I'd like to know who you 'are'. I'd like to have your helpful comments. The google 'widget' on the right lets me know that you're following this blog and will, I understand, keep you updated as to when I add a new blogpost—if you have a Google Dashboard. So please, do me a favor and 'sign up'. You can even do it anonymously, if you want to stay incognito.

Tuesday, September 9, 2008

Echoes of Time-Binding - I

Since Korzybski first formulated it in 1921 as the defining characteristic of humaness, others have used the notion of time-binding in their own formulating or have pointed to some aspect of the phenomena, with or without using the term.

For example, Richard Feynman referred to "time-binding" in answering the question "What is Science" Although time-binding had an important role in his answer to that question he apparently didn't consider it important enough to find out who coined the term. To me that seems like teaching the classical laws of motion and not bothering to mention Galileo or Newton. A physics teacher would not be doing his proper job, in my opinion, if he taught that way. But I get the distinct sense from reading other works by Feynman that he was not well-read or very knowlegable in areas outside of his own work and indeed didn't seem to consider any knowledge outside of physics as very worthwhile or even as science. But he had somehow heard about "time-binding." Curious.

For example, Richard Feynman referred to "time-binding" in answering the question "What is Science" Although time-binding had an important role in his answer to that question he apparently didn't consider it important enough to find out who coined the term. To me that seems like teaching the classical laws of motion and not bothering to mention Galileo or Newton. A physics teacher would not be doing his proper job, in my opinion, if he taught that way. But I get the distinct sense from reading other works by Feynman that he was not well-read or very knowlegable in areas outside of his own work and indeed didn't seem to consider any knowledge outside of physics as very worthwhile or even as science. But he had somehow heard about "time-binding." Curious.

Sunday, August 31, 2008

From Korzybski's Scrapbook, 1936 "A Distinguished Visitor"

Korzybski and his wife kept scrapbooks where they pasted newspaper clippings, articles, and other items related to their work. Here is an item from one of Korzybski's scrapbooks from April 1936: the front page of a mimeographed newsletter from the Marlboro State [Psychiatric] Hospital, where Korzybski lectured on April 9 of that year. This was almost three years after the publication of his book Science and Sanity, and two years before the founding of the Institute of General Semantics. The newsletter, the "Marlborogram" appears to have been intended for staff and patients. The account of Korzybski's talk under the heading of "A Distinguished Visitor" seems notable for its brief depiction of his work, which actually manages to convey quite a lot, and jibes with other accounts of his platform presence at the time:

Count Alfred Korzybski delivered a two hour lecture at the hospital before an audience of some fifty people last Thursday afternoon, April 9. Those present included the Staff doctors, representatives from the Central Department and the Business Department, nurses, patients and their friends and relatives. The Count, author of Science and Sanity, gave his lecture in the interests of the work in Semantics which is being developed in the Hospital by one of the Staff doctors.

To many present its was a memorable occasion. The speaker had a dashing and colorful personality. His energy was unbounded. Within the two hour period he gave clearly and forcefully a succinct account of his system of

General Semantics which, in his book Science and Sanity, requires over seven hundred pages for a detailed presentation.

As pointed out by the Count, our difficulties, both personal and public, are caused by false knowledge. Since knowledge is chiefly a question of proper language response, all that is needed to remove false knowledge with its attendant evils is to revise the structure of our present antiquated language with its primitive metaphysics. To do this one has to utilize only three basic facts – 1. the Map is not the Territory, 2. the Map does not cover all the characteristics of the Territory, 3. the Map is Self-Reflexive. What may be said of maps can also be said of Language. Utilizing certain devices from Mathematics, which he declares to be the finest language man has yet produced, one is then able to prepare a map-language which is similar in structure to the world in which we live. And when we have a language similar in structure to our world and our nervous system then false knowledge is removed with its resulting consequences.

Following dinner at the home of Dr. Graves the Count returned in the evening to his residence in New York City.

Thursday, August 28, 2008

The Gap, The Gap, Oh, The Gap....

In his 1921 book Manhood of Humanity, Korzybski had observed the gap between the advancing scientific/technological progress and the limited social/ethical progress of mankind. Or should I say man-unkind? This gap, he posited would grow and grow and lead to more deadly future disruptions—wars, revolutions, wars, revolutions, etc.—until humanity somehow found how to consciously appropriate its time-binding potential and carry it into all areas of human life, not just science and technology. Indeed, Korzybski's desire to close the deadly gap in human affairs drove him to develop general semantics.

As the Second World War was coming to a close in 1944 and 1945, he felt a certain amount of ruefulness, frustration, pessimism at the waste of human life, the suffering, the destruction of Poland, the mass-murder of European Jewry, the insanity of Nazism, etc. Many people at the time felt similarly. The writer Ben Hecht, contemplating his lost Jewish 'brothers' and 'sisters', sadly expressed it like this, in his bookA Guide for the Bedeviled:

As the Second World War was coming to a close in 1944 and 1945, he felt a certain amount of ruefulness, frustration, pessimism at the waste of human life, the suffering, the destruction of Poland, the mass-murder of European Jewry, the insanity of Nazism, etc. Many people at the time felt similarly. The writer Ben Hecht, contemplating his lost Jewish 'brothers' and 'sisters', sadly expressed it like this, in his bookA Guide for the Bedeviled:

If civilization is to be measured by the progress of human rationality, we can still use the yardstick of the cynic—which is no longer than a sigh.And yet... Korzybski wasn't inclined to say "people are bad, the world is bad, etc." and thus to sink into depression and despair. As he said 'I was born with a good liver'. He did say this: "The world is hopeless." Unless we as individuals work at changing the way we 'think' about 'things'. Then we might have some legitimate hope. Are we there yet?

Friday, August 22, 2008

Maps and Territories of the Beijing Olympics

Here you can see the Running Man logo of the Beijing Olympics—in the cross-hairs of a rifle scope.

Do I have your attention now?

Korzybski presented three fundamental new non-aristotelian premises for consciously evaluating humans:

1. A map is not the territory.

2. A map covers not all characteristics of the territory.

3. Mapping constitutes a potentially self-reflexive process, i.e., you can revise a map, i.e., make a map of a map, and a map of that map, etc.

Now when he was talking about maps, he wasn't talking about just geography maps, he was referring to any sort of representation, which could include the images you see on television, movie, newspapers and websites, what someone says or writes, what you perceive when you look out of the window, your favorite or un-favorite belief system, etc.

Korzybski's three premises, interconnected, serve as guides, heuristics that we can use as we navigate through the territory of life because...let's face it, don't fool yourself...you can't navigate without some kind of maps. Premise number 2 reminds us to remember to ask: What is getting left out of this or that particular map? Am I missing something important? What else should I know about what's going on here?

If you've been watching and enjoying the coverage on television of the Beijing Olympics, those questions also apply: What has the coverage left out? And, if there exists some systematic way in which some things have not been covered, how has that happened? and who are responsible?

Mark Alexander has written an article about some important things left out of the mainstream media Olympic coverage. He presents a valuable (in my opinion) map of the maps we have gotten on television and elsewhere. Enjoy the rest of the Olympics this weekend and read China's Porcelain Facade

Thursday, August 14, 2008

"Are You A Skeptic?"

According to the Blogthings Quiz below, I qualify as only a 67% Skeptic. Oh My! Perhaps I answered "not sure" for too many of the questions to get a higher score. Korzybski (who felt rather skeptical about 'skeptics') suggested the wisdom in doubting one's doubt. Some (NOT ALL) of the most dogmatic people I've known were members of skeptic's groups and atheist societies. So I don't feel so bad about not getting 100%. Korzybski File Readers, Let me know how you score if you take the test. I'm curious. — B.I.K.

You Are 67% Skeptic |

While you aren't always skeptical, you generally approach life from a skeptical viewpoint. You're open to any outlandish claim, but you need proof before you'll believe it. That being said, you're occasionally willing to go out on a limb and put your faith in idea. There's a few beliefs you hold because you hope they're true - not because they've been established as true. |

Thursday, August 7, 2008

"Language of Spirit"

My friend Richard Austin told me about the upcoming "Language of Spirit" conference related to the concerns of David Bohm in Albuquerque starting Saturday through the 12th. Physicist Bohm was fond of reminding people that "a map is not the territory" it represents.

The conference brings together Native American scientists, physicists, and other interested people. Richard has been attending for the past several years.

Another friend, Andy Hilgartner is presenting there this year. You may want to check out the program on their web site Language of Spirit.

The conference brings together Native American scientists, physicists, and other interested people. Richard has been attending for the past several years.

Another friend, Andy Hilgartner is presenting there this year. You may want to check out the program on their web site Language of Spirit.

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

Chain Reaction: A Dramatic Demonstration

After World War II, the atomic bomb—the awesome and awful weapon that had ended the war— had a lot of people's attention and interest. How did it work? Enrico Fermi had said in an interview that the secret of the bomb could be stated in two words, "exponential function." The atomic bomb provided only one example of exponential functions in operation. They seemed ubiquitous throughout nature, including the world of human affairs.

Indeed, as readers of the previous blogposts here on time-binding know, Korzybski had proposed in 1921 that time-binding too, involved an exponential function. By 1947 mousetrap models of the chain reaction in an 'atomic bomb' began to get written about in journals and even the popular media. Korzybski read about the "Atomic Mousetraps" in Science News and decided that he had to have one in his seminars to demonstrate this important notion of chain reactions. For him it wasn't sufficient to explain 'concepts' like this, they had to be seen, heard and felt to 'get under the skin' of his students.

The demonstration he used in his 1948-1949 Winter Intensive seminar involved an array of mousetraps set up in a large box with a glass front for viewing and a closed top (for protection) with a hole in it. The traps were set and arranged on the floor of the box in columns of about 5 traps arranged in cross-rows of 10 or so in close proximity. Two hard candies, representing 'neutrons' had been balanced on the spring of each trap. Then Ralph Hamilton, Korzybski's assistant at the time, dropped another single 'neutron' candy (raspberry flavored, by the way) through the hole in the top of the box to trigger one trap below, which sent its two 'neutrons' flying through the air. Each one set off another two neutrons, and so on. Within a few seconds the whole 'bomb' of about 50 mousetrap 'atoms' had exploded with dramatic results.

The YouTube video below shows a demonstration which, although it uses single pingpong balls, will give you a pretty good feel for what Korzybski's seminar students might have seen.

Exponential Function Visualized.

Indeed, as readers of the previous blogposts here on time-binding know, Korzybski had proposed in 1921 that time-binding too, involved an exponential function. By 1947 mousetrap models of the chain reaction in an 'atomic bomb' began to get written about in journals and even the popular media. Korzybski read about the "Atomic Mousetraps" in Science News and decided that he had to have one in his seminars to demonstrate this important notion of chain reactions. For him it wasn't sufficient to explain 'concepts' like this, they had to be seen, heard and felt to 'get under the skin' of his students.

The demonstration he used in his 1948-1949 Winter Intensive seminar involved an array of mousetraps set up in a large box with a glass front for viewing and a closed top (for protection) with a hole in it. The traps were set and arranged on the floor of the box in columns of about 5 traps arranged in cross-rows of 10 or so in close proximity. Two hard candies, representing 'neutrons' had been balanced on the spring of each trap. Then Ralph Hamilton, Korzybski's assistant at the time, dropped another single 'neutron' candy (raspberry flavored, by the way) through the hole in the top of the box to trigger one trap below, which sent its two 'neutrons' flying through the air. Each one set off another two neutrons, and so on. Within a few seconds the whole 'bomb' of about 50 mousetrap 'atoms' had exploded with dramatic results.

The YouTube video below shows a demonstration which, although it uses single pingpong balls, will give you a pretty good feel for what Korzybski's seminar students might have seen.

Exponential Function Visualized.

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

"Time-Binding" : An Overview & Review

Here in one convenient place, I have put the previous postings I've done on Alfred Korzybski's formulation of time-binding. "Time-Binding" the subject of Korzybski's first book, Manhood of Humanity (1921), provided the foundation of what he subsequently formulated, as he sought to understand the mechanism of time-binding—how it works and how can we get it to work better. He felt profoundly convinced that, as he used to say 'Man is not an animal!'

Following each linked post below, in order, will give the reader a short but comprehensive overview of time-binding: how Korzybski developed it, his motivation for doing so, his unique approach to the phenomenon of human behavior,

implications of the notion of time-binding, previous viewpoints touching on the subject, etc.

What you read below is based on a careful, long-term study of Korzybski's writings, including rarely seen material from the Korzybski archives.

Remember, you're reading about yourself. What's in it for you?

...and the vermin were humans...and the streetcar

Korzybski's Formulation of "Time-Binding"

More on Time-Binding

Time-Binding and the Language and Logic of Nature

Man As An Exponential Power

Consequences of Time-Binding (Part I)

Consequences of Time-Binding (Part II)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part I)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part II)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part III)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part IV)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part V)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part VI)

Following each linked post below, in order, will give the reader a short but comprehensive overview of time-binding: how Korzybski developed it, his motivation for doing so, his unique approach to the phenomenon of human behavior,

implications of the notion of time-binding, previous viewpoints touching on the subject, etc.

What you read below is based on a careful, long-term study of Korzybski's writings, including rarely seen material from the Korzybski archives.

Remember, you're reading about yourself. What's in it for you?

...and the vermin were humans...and the streetcar

Korzybski's Formulation of "Time-Binding"

More on Time-Binding

Time-Binding and the Language and Logic of Nature

Man As An Exponential Power

Consequences of Time-Binding (Part I)

Consequences of Time-Binding (Part II)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part I)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part II)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part III)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part IV)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part V)

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part VI)

Friday, July 11, 2008

Simulation, Shmimulation

"The map is not the territory! The map is not the territory! The map is not the territory! Oh, Boy, oh boy, oh boy— I'm confused! I'm confused! "

The Age of Simulation: Phony Transcendence in an Age of Media,

Computers and Fabricated Environments

Friday, July 4, 2008

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part VI)

Interest in the idea of “progress” had become widespread by the mid-19th Century due in part to the work of Auguste Comte, founder of the discipline of sociology and of “positive philosophy.” Korzybski’s distinction between the childhood and the manhood of humanity echoed Comte’s discussion of the three phases in the development of human knowledge: the Theological, the Metaphysical, and the Scientific or “Positive” stages. The flavor of optimism and sense of the inevitability of human progress expressed by Comte seem clearly present in Manhood of Humanity as well.

By the late 19th Century, in his work Progress and Poverty (a volume in Korzybski’s personal library), American political economist Henry George, demonstrated a sense of both the transmission of culture and of progress, consistent with the notion of time-binding.

Granted, he stood on their shoulders. Still Korzybski’s formulation of time-binding did something new. It brought together under one unifying, functional formulation the various related factors that others had previously noted. Making time-binding, the distinguishing feature of the human class of life gave the phenomenon a greater significance. His formula PRT and his emphasis on the implications and applications of conscious time-binding for human welfare gave added value to the formulation. It seemed to him that his new definition, with these accompanying aspects, constituted a proper starting point for an applied science of humanity—a new art and science of human engineering.

By the late 19th Century, in his work Progress and Poverty (a volume in Korzybski’s personal library), American political economist Henry George, demonstrated a sense of both the transmission of culture and of progress, consistent with the notion of time-binding.

The narrow span of human life allows the individual to go but a short distance, but though each generation may do but little, yet generations, succeeding to the gain of their predecessors, may gradually elevate the status of mankind, as coral polyps, building one generation upon the work of the other, gradually elevate themselves from the bottom of the sea. (1)Then in the first decade of the 20th Century, writer Henry Adams—noting the breathtaking changes brought on by expanding scientific knowledge and technological advances—had suggested a historical law of acceleration to account for them. Adams did not supply an actual equation, although he did suggest its exponential nature. Clearly, the main factors that entered into Korzybski’s formulation of time-binding had been recognized by many others before him.

Granted, he stood on their shoulders. Still Korzybski’s formulation of time-binding did something new. It brought together under one unifying, functional formulation the various related factors that others had previously noted. Making time-binding, the distinguishing feature of the human class of life gave the phenomenon a greater significance. His formula PRT and his emphasis on the implications and applications of conscious time-binding for human welfare gave added value to the formulation. It seemed to him that his new definition, with these accompanying aspects, constituted a proper starting point for an applied science of humanity—a new art and science of human engineering.

Friday, June 27, 2008

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part V)

In his manuscript and book, Korzybski had observed that

Notes

(1). Manhood of Humanity (1921), p.111.

(2). "Discoveries and inventions: A lecture delivered by Abraham Lincoln in 1860." (1915), San Francisco: John Howell. Also available at << http://showcase.netins.net/web/creative/lincoln/speeches/discoveries.htm >> (accessed 5/31/2006). Lincoln gave another version of this speech in February 1859 (see The Library of America’s Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings 1859-1865, pp. 3-11.) Lincoln appeared devoted to the subject but the lecture was generally not considered a success (See Harold Holzer’s Lincoln At Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President, pp 19-20, 210.)

(3). Ibid.

…in animal life time does not play the role it plays in human life. Animals are limited by death permanently. If animals make any progress from generation to generation, it is so small as to be negligible. A beaver, for example, is a remarkable builder of dams, but he does not progress in the way of inventions or further development. A beaver dam is always a beaver dam. (1)There is no indication that he was aware at the time he wrote this of Abraham Lincoln’s “Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions” first delivered in 1858. In this lecture, Lincoln clearly pointed out the difference between humans and animals (also using the example of beavers) that Korzybski had observed.:

All creation is a mine, and every man, a miner…In the beginning, the mine was unopened, and the miner stood naked, and knowledgeless, upon it. Fishes, birds, beasts, and creeping things, are not miners, but feeders and lodgers, merely. Beavers build houses; but they build them in nowise differently, or better now, than they did, five thousand years ago. Ants, and honey-bees, provide food for winter; but just in the same way they did, when Solomon referred the sluggard to them as patterns of prudence. Man is not the only animal who labors; but he is the only one who improves his workmanship. This improvement, he effects by Discoveries, and Inventions.(2)In the rest of his speech Lincoln provided a brief history and discussion of the conditions of human progress as he saw it. Lincoln noted the importance that cooperation, the use of speech, and the inventions of writing and the printing press, had in the sharing and transmission of knowledge. He pointed out a given generation’s dependence on the discoveries and inventions of the past, including the discovery and invention of methods of discovery and invention. He also mentioned the accelerating aspect of the growth of human knowledge especially notable after the invention of the printing press: “…discoveries, inventions, and improvements followed rapidly and have been increasing their rapidity since.”(3)

Notes

(1). Manhood of Humanity (1921), p.111.

(2). "Discoveries and inventions: A lecture delivered by Abraham Lincoln in 1860." (1915), San Francisco: John Howell. Also available at << http://showcase.netins.net/web/creative/lincoln/speeches/discoveries.htm >> (accessed 5/31/2006). Lincoln gave another version of this speech in February 1859 (see The Library of America’s Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings 1859-1865, pp. 3-11.) Lincoln appeared devoted to the subject but the lecture was generally not considered a success (See Harold Holzer’s Lincoln At Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President, pp 19-20, 210.)

(3). Ibid.

Thursday, June 19, 2008

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part IV)

By the mid-1800s, some notion of the process of transmission basic to time-binding had become widely accepted. George Boole, creator of the first system of mathematical logic, was able to clearly describe it in this passage from his address on “The Social Aspects of Intellectual Culture” to the Cuvierian Society, a science club in Cork, Ireland:

Note

(1) George Boole, qtd.George Boole: His life and work. By Desmond MacHale. Dublin: Boole Press (1985), p. 123.

Each generation as it passes away bequeathes to its successor not only its material works in stone and marble, in brass and iron, but also the truths which it has won, and the ideas which it has learned to conceive; its art, literature, science, and, to some extent, its spirit and morality. This perpetual transmission of the light of knowledge and civilization has been compared to those torch races of antiquity in which a lighted brand was transmitted from one runner to another until it reached the final goal. Thus it has been said do generations succeed each other, borrowing and conveying light, receiving the principles of knowledge, testing their truth, enlarging their application, adding to their number, and then transmitting them forward to coming generations—Et quasi cursores vitai lampada tradunt [And like runners they pass on the torch of life]. (1) [Boole was quoting a line from De Rerum Natura by the poet-philosopher Lucretius who lived from 99 B.C.E.–55 B.C.E.. Greeks like Lucretius, not surprisingly, had also recognized aspects of the process of time-binding, almost 2 millennia before.]

Note

(1) George Boole, qtd.George Boole: His life and work. By Desmond MacHale. Dublin: Boole Press (1985), p. 123.

Friday, June 13, 2008

Forerunners to the Time-Binding Notion (Part III)

Korzybski’s study of the humanist tradition of Europe, strongly represented in Poland, probably exerted a direct effect on Alfred’s formulation of the time-binding notion. Renaissance thinkers like Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1518) showed how one could acknowledge and learn from the past to develop one’s excellence in the present and in this way contribute to future generations. In his 1902 biographical novel, The Romance of Leonardo da Vinci (English translation 1928), Russian writer Dmitri Merejkowski described a passage from da Vinci’s notebooks:

Once, desiring to present the development of human spirit, he drew a row of cubes: the first, falling, knocks down the second; the second, a third, the third, a fourth, and so on, ad infinitum. Underneath he wrote: “One jolts the other.” And he also added: “The cubes designate the generations of mankind and the stages of its knowledge.” On another drawing he represented a plough, turning up the earth, with the inscription: “Persistent Rigour.” He believed that his turn, too, would come in the row of falling cubes, — that at some time or other men would respond to his summons also. (p. 345)Korzybski had long had the habit of reading a book by studying its author. His formulation of time-binding generalized this and thereby continued the humanist theme of the human origins of human culture. It implied that any aspect of culture had an author—in fact multiple authors. In his later writing and teaching, Alfred would often emphasize art, mathematics, religion, science, etc., as “manmade and nothing but.” This didn’t necessarily make them dependant on entirely arbitrary foundations but, on the contrary, seemed to provide a necessary approach for understanding, appropriating, and using them more effectively. And revising them when needed.

Thursday, May 29, 2008

Einlauf Soup

I got an email the other day from my good friend Clayton Mitchum. Clayton's not very familiar with the GS lingo but his story shows the difference between verbal 'meanings' or definition (more the subject of traditional 'semantics') versus non-verbal evaluation, i.e., 'semantic [evaluational] reaction' the subject of general semantics. We respond to words, symbols, indeed any events in terms of such organism-as-a-whole reactions. Clayton gave me permission to post his email here:

Bruce,

I was on the phone yesterday with your Mt. Lebanon classmate, Bill F. I think the last time you and I discussed Bill, we weren’t speaking, but now we are talking again. Anyway, he was asking about you and what you were doing, and I told him about your book and semantics. He then reminded me of a story I’d told him years ago – that’s the weird thing about Bill – he remembers everything from years ago, but he can’t remember what he did yesterday. I thought you might be interested in this.

My great-grandfather was a translator for the Prussian court. Not only was he present to translate at every discussion between visiting dignitaries speaking various languages, but also dignitaries who spoke the same language; i.e., German. He always told the family (he died before I was born) that there were probably more misunderstandings between folks speaking the same language than different ones, because of semantics. That example came driving home to Rosanne and me a few years ago.