Korzybski: A Biography (Free Online Edition)

Copyright © 2014 (2011) by Bruce I. Kodish

All rights reserved. Copyright material may be quoted verbatim without need for permission from or payment to the copyright holder, provided that attribution is clearly given and that the material quoted is reasonably brief in extent.

“The teacher who walks in the shadow of the temple, among his followers, gives not of his wisdom but rather of his faith and lovingness. If he is indeed wise he does not bid you enter the house of his wisdom, but rather leads you to the threshold of your own mind.”

—Khalil Gibran, “On Teaching”, The Prophet (1)

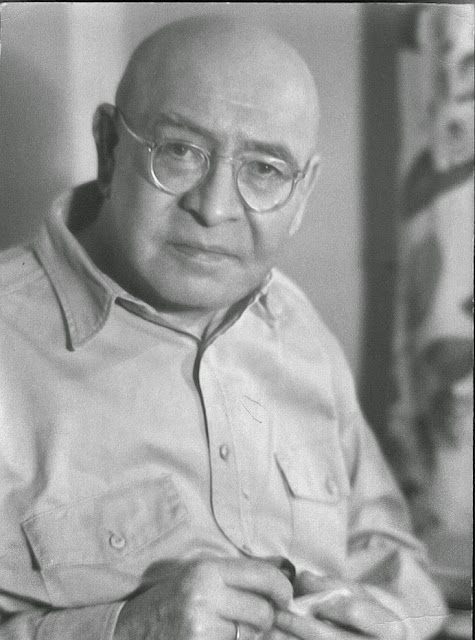

About 60 people from around the United States and Canada came to Connecticut for the memorial service at the Institute on Saturday, March 4, 1950. Since she could not come, Mira sent in her stead, an arrangement of flowers molded in the shape of a five-pointed star. One of her nicknames, “The Wonder Star”, had come from the variable star discovered in 1905 that astronomers had named “Mira”.(2) The flower star—indicating Mira’s presence—was placed at the head of the plain open coffin where Alfred’s corpse lay wearing his glasses and the khaki attire he had favored.

As they gathered, guests heard some of the music Alfred loved best: recordings of the Sixth (Pathetique) Symphony of his favorite composer, Tchaikovsky; Asa’s Death by Grieg; and Siegfreid’s Funeral March from Wagner’s Die Gotterdammerung (which Korzybski liked in spite of its Nazi echoes). Then Ralph Hamilton sang Hugo Wolf’s Weyla’s Song.

Kendig and Charlotte wanted Bob Redpath to conduct the service. Kendig had told him,

The quote from the Preface to Schrodinger’s book What is Life? seemed to Redpath an especially fitting description of Korzybski’s lifework:

Soon afterwards, an autopsy—as Korzybski had arranged for— was done by an associate of his long-time friend, Doctor Nolan D. C. Lewis, at that time Director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Hospital. (Lewis was ill and could not come to do it himself.) Korzybski had observed many autopsies Lewis conducted at St. Elizabeths Hospital when both worked there in the mid-1920s. Both men had an interest in the relations—even sketchier in 1950 than now—between brain, behavior and consciousness. Dr. Lewis, who had looked at and handled many human brains, later reported the observations of Korzybski’s brain:

Ernest R. Schaefer, a Yale University art student whom Bob Redpath found, had already made a death mask and casted both of Korzybski’s hands. With the help of those notably large and supple hands, Korzybski had done his job; now he himself was done. Others would have to carry on.

“The teacher who walks in the shadow of the temple, among his followers, gives not of his wisdom but rather of his faith and lovingness. If he is indeed wise he does not bid you enter the house of his wisdom, but rather leads you to the threshold of your own mind.”

—Khalil Gibran, “On Teaching”, The Prophet (1)

About 60 people from around the United States and Canada came to Connecticut for the memorial service at the Institute on Saturday, March 4, 1950. Since she could not come, Mira sent in her stead, an arrangement of flowers molded in the shape of a five-pointed star. One of her nicknames, “The Wonder Star”, had come from the variable star discovered in 1905 that astronomers had named “Mira”.(2) The flower star—indicating Mira’s presence—was placed at the head of the plain open coffin where Alfred’s corpse lay wearing his glasses and the khaki attire he had favored.

As they gathered, guests heard some of the music Alfred loved best: recordings of the Sixth (Pathetique) Symphony of his favorite composer, Tchaikovsky; Asa’s Death by Grieg; and Siegfreid’s Funeral March from Wagner’s Die Gotterdammerung (which Korzybski liked in spite of its Nazi echoes). Then Ralph Hamilton sang Hugo Wolf’s Weyla’s Song.

Kendig and Charlotte wanted Bob Redpath to conduct the service. Kendig had told him,

...both Charlotte and I believe that you will do it simply and with dignity, and that he would have liked you to do it. You may not know all that there is to know about GS but you will give the feeling that you have for him, and that he sensed. And that is what we want. (3)Redpath read passages from Khalil Gibran’s The Prophet (extracts from “On Teaching” and “Farewell to the People of Orphalese”); Proverbs 3:13-18; Chapter 13 of First Corinthians (which to Redpath seemed to fittingly “refer to the faith-love that underlay the personality [of Alfred] and the effort towards mankind underlying his whole life-work)”(4); Erwin Schrodinger; Ivan Pavlov; and, from Korzybski’s own writings, Manhood of Humanity and the “Preface to the Third Edition” of Science and Sanity.

The quote from the Preface to Schrodinger’s book What is Life? seemed to Redpath an especially fitting description of Korzybski’s lifework:

We have inherited from our forefathers the keen longing for unified, all-embracing knowledge. The very name given to the highest institutions of learning reminds us, that from antiquity and throughout many centuries the universal aspect has been the only one to be given full credit. But the spread, both in width and in depth, of the multifarious branches of knowledge during the last hundred years has confronted us with a queer dilemma. We feel clearly that we are only now beginning to acquire reliable material for welding together the sum-total of all that is known into a whole; but, on the other hand, it has become next to impossible for a single mind fully to command more than a small specialized portion of it.The service closed with the playing of the fourth movement (a funeral march) of Tchaikovsky’s Manfred that Korzybski had often enjoyed listening to in the evening hours with friends. In a statement that Redpath read beforehand to those assembled, Charlotte had written:

I can see no other escape from this dilemma (lest our true aim be lost forever) than that some of us should venture to embark on a synthesis of facts and theories, albeit with second-hand and incomplete knowledge of them—at the risk of making fools of ourselves. (5)

...Usually when we played music in the evenings,...he said, ‘Let’s end with a funeral march.’...[Alfred] particularly loved the dramatic poem ‘Manfred’ by Byron and the music which Tchaikovsky composed to it...Manfred, the hero of Byron’s poem seemed to Alfred as one who was ceaselessly and passionately in quest, searching, searching, and who refused ever to surrender; and while listening to the music Alfred used to make a large question mark in the air with his hand : ‘Why, why, what is it all about?’ Toward the end of the symphony, the music comes to a climax, and the death of Manfred is at hand, and then follows the beautiful, solemn and peaceful finale. (6)

Soon afterwards, an autopsy—as Korzybski had arranged for— was done by an associate of his long-time friend, Doctor Nolan D. C. Lewis, at that time Director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Hospital. (Lewis was ill and could not come to do it himself.) Korzybski had observed many autopsies Lewis conducted at St. Elizabeths Hospital when both worked there in the mid-1920s. Both men had an interest in the relations—even sketchier in 1950 than now—between brain, behavior and consciousness. Dr. Lewis, who had looked at and handled many human brains, later reported the observations of Korzybski’s brain:

It showed some of the normal shrinkage due to the age of the man, but it had a very rich blood supply which is significant and a complex convolutional arrangement which will be very important to study in detail, as it is the brain of a great scientist. (7)Alfred’s cremated remains were buried in a little cemetery in Lime Rock, in a simple grave, marked with the Ā (non-A) symbol representing the non-aristotelian system he had formulated and taught. (Alfred’s beloved Mira, without whose urgings and help he would never have produced his work, died four years later. As both had wished, her remains were buried next to his.)

Ernest R. Schaefer, a Yale University art student whom Bob Redpath found, had already made a death mask and casted both of Korzybski’s hands. With the help of those notably large and supple hands, Korzybski had done his job; now he himself was done. Others would have to carry on.

|

| Death Mask of Alfred Korzybski by Ernest R. Schaefer of Yale University School of Art |

Notes

You may download a pdf of all of the book's reference notes (including a note on primary source material and abbreviations used) from the link labeled Notes on the Contents page. The pdf of the Bibliography, linked on the Contents page contains full information on referenced books and articles.

1. Gibran, p. 64, qtd. in “Memorial Service for Alfred Korzybski, Four March 1950”, General Semantics Bulletin 3 (1950), p. 14.

2. David Linwood [Levine], personal communication.

3. Qtd. in Redpath, Vol. II. p. 69.

4. Redpath, Vol. II. p. 71.

5. Schrodinger, p. vii, qtd. in “Memorial Service for Alfred Korzybski”, General Semantics Bulletin 3 (1950), p. 14.

6. “Memorial Service for Alfred Korzybski”, Ibid., p. 13.

7. Qtd. in Schuchardt 1950, p. 40.