Korzybski: A Biography (Free Online Edition)

Copyright © 2014 (2011) by Bruce I. Kodish

All rights reserved. Copyright material may be quoted verbatim without need for permission from or payment to the copyright holder, provided that attribution is clearly given and that the material quoted is reasonably brief in extent.

With the seminar done in early September, Korzybski and the Institute staff returned to Lime Rock. The atmosphere of bedlam after the Congress while preparing for the seminar had ceased, but the small staff still seemed mightily busy, if not overwhelmed, with work. Mac Mallach had been joined in June by a new office assistant Henrietta Vandervoort. “Miss Van”, as she was called, managed the 8,000-name student and general mailing lists and stencils, and did the general correspondence filing as well as secretarial work for Charlotte. As 1949 was drawing to a close, she may have helped to keep Charlotte and Kendig sane—and thus everyone else as well. Like many people in the U.S., their nerves were probably a little on edge anyway. On September 23 came ominous news: President Truman confirmed that Stalinist Russia had exploded an atomic bomb. In China, with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces forced to retreat to Taiwan, the Communists under Mao Zedong had won the Civil War. On October 1, Mao declared a “People’s Republic” in Mainland China.

Still, they had good news at the Institute of General Semantics. Dave Bourland had just received the Korzybski Fellowship, which he had applied for in June. He would draw a stipend from the Institute and, along with his ongoing duties, would take on a few more responsibilities, and also presumably get more time to study with Korzybski. Among other things, along with Ralph Hamilton, he began working as an Assistant to Kendig, editing the Institute’s new publication, the General Semantics Bulletin (GSB)—with Lynn Gates in charge of production and cover-design.

Given its currently dicey relationship with the International Society and lack of control over ETC.’s editorial content, it seemed time for the Institute to bring out its own regular publication. GSB would serve as a more rigorous korzybskian alternative to ETC.’s watered-down approach. (In fairness to Hayakawa, he would continue to publish articles by more korzybskian writers like Allen Walker Read, Sam Bois, Ray Bontrager, etc., along with articles that people at the Institute would consider unsuitable from a non-aristotelian point of view.) Also by consolidating important articles into the GSB, the Institute could stop sending them out as separate mailings, and in that way save time, effort, and money. The first General Semantics Bulletin (Numbers One & Two)—a double issue for “Autumn-Winter 1949-1950” published for ‘Members of the Institute’ “for information and inter-communication among workers in the non-aristotelian discipline formulated by Alfred Korzybski” with “news, views, comments, group activities, work-in-progress reports, research and applications, etc.” and intended “to appear three or more times per year”—was ready for the printer by the end of February 1950. Korzybski would naturally know and have a say about whatever was going into this first issue, but he was not much involved with the editing or production.

Besides working directly with Alfred, Charlotte had other business needing her attention. For example, she was managing the production of the Institute’s two newest major publication items: Korzybski’s Time-Binding: The General Theory, Two Papers 1924–1926 with an introduction by Kendig, as well as the Structural Differential wall charts. By the end of October, both were produced and ready for official announcement and sale by the Institute. Charlotte also had a great deal of correspondence to catch up with—for one thing, correspondence with Ken Keyes (partly on behalf of Korzybski). Since 1947, Charlotte had been keeping tabs on the various aspects of Keyes’ proposed biography of Alfred and sending information and loaning materials to him that she hoped would facilitate his work on it. Keyes had just moved, started a new job, and finished his first book—How To Develop Your Thinking Ability, set to be published in 1950. It wasn’t clear how much progress he had made on the biography. Not much it turned out; though by this time his wife, Roberta had finished transcribing the recording of Korzybski’s 1947 memoir—not a small task in itself. Charlotte did what she could to help him and at the end of October, she wrote to fill him in on some important information she thought he should have for the biography:

Korzybski had his own backlog of correspondence, also the Manhood Introduction to finish, and in October a new project that fell into his lap—an invitation to speak at a psychology symposium at the University of Texas in Austin. He couldn’t refuse. The psychology department there had gotten a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to conduct an ongoing symposium on “Perception: A Focus for Personality Analysis”. Speakers would individually lecture in Texas from October 1949 until June 1950, each presenting a different aspect of the topic, which would constitute their contribution to a published book of the proceedings [Perception: An Approach to Personality]. Beforehand, they would each get a theoretical outline of the symposium by the organizers, Professors Robert R. Blake and Glenn V. Ramsey, who presented the first paper on “Perceptual Processes as Basic to an Understanding of Complex Behavior”. Each speaker would also get summaries of the preceding speakers’ presentations and would have the opportunity to revise their contribution for the book after all invited papers had been presented. Those invited included a number of significant and rising figures in the behavioral sciences. (One of the contributors, James G. Miller had only recently suggested “behavioral sciences” as a general integrating term for the life and social sciences). Besides Miller, the invited speakers included: Clifford T. Morgan, Frank A. Beach, Ernest R. Hilgard, Jerome S. Bruner, Wayne Dennis, Urie Brofenbrenner, Norman Cameron, Carl R. Rogers, George S. Klein, and Else Frenkel-Brunswik. Korzybski—the only non-academically connected, non-psychologist/non-psychiatrist in the bunch—was to give his presentation in the last week of January (the date later moved to early April). He would get an honorarium and travel expenses for the trip to Texas for both him and Charlotte. By means of his applied epistemological approach, Korzybski could probably have said something useful about any area related to “functional determinants of perceptual processes”, but his specific assignment focused on ‘the effect on perceptual processes of the language system”. He considered the invitation a great privilege and his contribution something worth sweating over. On the way back from Texas, he planned to stop in Chicago, where the GS group there wanted him to speak and he could also visit Mira. He would write his contribution, with Charlotte’s help, mainly over the first two months of 1950. But now as the end of the year approached, along with the annual Holiday Intensive, he wanted to see if he could get further along, even done, with the Introduction to Manhood. This meant another trip to New York City in November.

By this time, Mira had gotten fairly hobbled and pretty much housebound. She didn’t feel stable walking alone outside and needed help in the apartment as well. The young woman who had lived with her had left some time before. Mira wrote to Alfred about a 24-year- old medical student, Albert William Kneller, who had just started staying in the spare bedroom where Charlotte usually slept during visits. In exchange for the room and a small stipend, “Dr. Bill”—as Mira called him—was helping her with cooking, cleaning and other chores and would accompany her on those increasingly rare times when she left the apartment. Alfred, of course, felt concerned but with the help she received from her doctors, neighbors, etc., and now Dr. Bill, Mira still seemed to manage.

And despite her problems she seemed to maintain a positive outlook. She continued to write to Alfred often—little notes with memories of their earlier times together, references to his work, and interesting things she heard on the radio or read about. For instance, she had found this reference to time-binding in a collection of essays, Reflections On Our Age, newly published by UNESCO: Julian Huxley’s essay “A Re-definition of Progress”, referred to “the present culmination of life in the emergence of man—the microcosm, the time-binders with brain and mind capable of annihilating the sequence of events and tying them together in the unity of consciousness;...” As Mira noted, there was no direct reference to Alfred or his work.(55) Mira’s stream of references, suggestions, links, and leads both great and small had continued to exert an influence on the content of Alfred’s formulating. And if in his general mood he also seemed more mellow, perhaps even more hopeful—in spite of all the messes and problems he continued to observe or personally had to deal with—perhaps a little bit of Mira’s somewhat sunnier disposition had also gradually rubbed off on him. But she probably wasn’t trying to give him a subliminal message when she sent him a volume called Sunspots in Action, which she thought he might like to read. He telegrammed her on Thursday, November 17 (56):

Within a few days he and Charlotte were back at Hotel 33. Sometimes he just sat in his room alone, silently contemplating, visualizing what he still had left to say in the Manhood Introduction. Then he would talk things out with Charlotte, wrestling to get what he wanted into words; then having finally gotten something written, both of them would delouse it; and then the whole process would begin again. Over the past two years, as they had worked on the Introduction, Korzybski no doubt spent a fair amount of time contemplating the arc of his life’s work from its beginnings to the present. He sought to express that in the Introduction. The delay in getting it finished probably inspired frustration, but he knew the writing and editing process had to take its course. Earlier in the spring, also at Hotel 33, as he and Charlotte had worked away, he had jokingly said as she took notes, “This new introduction by Korzybski has been edited by me, as it was not finished.”(57) He surely intended this as a joke and not a prediction. Until the piece seemed good enough for publishing, he and Charlotte would have to push on with steady work. He wanted to get it done. So this extended period away from the distractions of Lime Rock seemed necessary. They stayed in New York for four and a half weeks.

Throughout this period, Charlotte kept Mira filled in on their progress. And as he sometimes did, Alfred would pencil-in short notes to Mira at the end of Charlotte’s letters. Just as Mira had pushed Alfred to write the book in the first place, she had ‘nagged’ him for years about the importance of time-binding when he had placed it to the side. Mira’s impetus had helped him to get re-engaged with the notion, and there was no one more eager than her to see the Second Edition in print once again.

A little more than two weeks into their stay, Charlotte wrote to her that Alfred had caught another ‘bug’, a chest cold, but otherwise he felt alright and was working hard. As Charlotte told her, the Introduction had a good structure in spite of that eternal—or infernal—delousing. They felt very anxious to have it done. Other than Alfred inviting 25 people up to their rooms for a December 7 cocktail party for Charlotte’s birthday, they didn’t appear to socialize or go out much. One visitor, Dr. Wolf, a student of Alfred’s from the last summer seminar, came socially but also examined Alfred and prescribed some quinine, which seemed to help his cold. Wolf also told them about a friend of his, photographer Lotte Jacobi, who had photographed many writers, artists, and scientists in Weimer Germany and, as a Jew, had escaped to the U.S. before World War II and was now living in New York. She was interested in Alfred’s work and wanted to take his picture. Alfred didn’t object, Charlotte contacted her, and Lotte Jacobi came to Hotel 33 sometime during the next few weeks to do so.

Charlotte and Alfred had gone through at least several more drafts and had gotten the Introduction into what Charlotte considered pretty good shape. But they still hadn’t finished it by the next-to-last week in December when they had to get back to Lime Rock. With the Holiday Intensive at the Sharon Inn starting on December 26, they needed several days to prepare and on Christmas had to get themselves and the seminar stuff moved to the Inn, even though it was only a few miles away. So they returned on December 21. When they got home they found that Kendig had been admitted to the Sharon Hospital, apparently due to exhaustion. Typical of her, she had already done the seminar planning, assigned tasks to the staff, and left a memo with the details for Alfred and Charlotte. She was out of the hospital in a few days. She would stay at the house but was able to participate in the seminar, coming over for part of the day and having lunch and dinner at the Inn with Alfred, Charlotte, and the others. Thank goodness they had a small group. The seminar went well. Alfred did a good job, seemed jovial and sharp, even if he no longer paced the room nor made points by brandishing his cane or stamping it on the floor. On December 22, just before the seminar started, he had sent out a special invitation letter to friends and trustees to attend the New Year’s Party, which might indicate his mood:

With Mira’s birthday on January 16, and her and Alfred’s 31st wedding anniversary on January 17, 1950, a flurry of congratulatory telegrams and notes in the mail went back and forth for several days between Chicago and Lime Rock. The Institute staff drank with Alfred to Mira’s birthday and their anniversary. Mira and Dr. Bill toasted to her and Alfred on glasses of orange juice. Alfred sent a handwritten note to Mira (59):

With the seminar done in early September, Korzybski and the Institute staff returned to Lime Rock. The atmosphere of bedlam after the Congress while preparing for the seminar had ceased, but the small staff still seemed mightily busy, if not overwhelmed, with work. Mac Mallach had been joined in June by a new office assistant Henrietta Vandervoort. “Miss Van”, as she was called, managed the 8,000-name student and general mailing lists and stencils, and did the general correspondence filing as well as secretarial work for Charlotte. As 1949 was drawing to a close, she may have helped to keep Charlotte and Kendig sane—and thus everyone else as well. Like many people in the U.S., their nerves were probably a little on edge anyway. On September 23 came ominous news: President Truman confirmed that Stalinist Russia had exploded an atomic bomb. In China, with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces forced to retreat to Taiwan, the Communists under Mao Zedong had won the Civil War. On October 1, Mao declared a “People’s Republic” in Mainland China.

Still, they had good news at the Institute of General Semantics. Dave Bourland had just received the Korzybski Fellowship, which he had applied for in June. He would draw a stipend from the Institute and, along with his ongoing duties, would take on a few more responsibilities, and also presumably get more time to study with Korzybski. Among other things, along with Ralph Hamilton, he began working as an Assistant to Kendig, editing the Institute’s new publication, the General Semantics Bulletin (GSB)—with Lynn Gates in charge of production and cover-design.

Given its currently dicey relationship with the International Society and lack of control over ETC.’s editorial content, it seemed time for the Institute to bring out its own regular publication. GSB would serve as a more rigorous korzybskian alternative to ETC.’s watered-down approach. (In fairness to Hayakawa, he would continue to publish articles by more korzybskian writers like Allen Walker Read, Sam Bois, Ray Bontrager, etc., along with articles that people at the Institute would consider unsuitable from a non-aristotelian point of view.) Also by consolidating important articles into the GSB, the Institute could stop sending them out as separate mailings, and in that way save time, effort, and money. The first General Semantics Bulletin (Numbers One & Two)—a double issue for “Autumn-Winter 1949-1950” published for ‘Members of the Institute’ “for information and inter-communication among workers in the non-aristotelian discipline formulated by Alfred Korzybski” with “news, views, comments, group activities, work-in-progress reports, research and applications, etc.” and intended “to appear three or more times per year”—was ready for the printer by the end of February 1950. Korzybski would naturally know and have a say about whatever was going into this first issue, but he was not much involved with the editing or production.

Besides working directly with Alfred, Charlotte had other business needing her attention. For example, she was managing the production of the Institute’s two newest major publication items: Korzybski’s Time-Binding: The General Theory, Two Papers 1924–1926 with an introduction by Kendig, as well as the Structural Differential wall charts. By the end of October, both were produced and ready for official announcement and sale by the Institute. Charlotte also had a great deal of correspondence to catch up with—for one thing, correspondence with Ken Keyes (partly on behalf of Korzybski). Since 1947, Charlotte had been keeping tabs on the various aspects of Keyes’ proposed biography of Alfred and sending information and loaning materials to him that she hoped would facilitate his work on it. Keyes had just moved, started a new job, and finished his first book—How To Develop Your Thinking Ability, set to be published in 1950. It wasn’t clear how much progress he had made on the biography. Not much it turned out; though by this time his wife, Roberta had finished transcribing the recording of Korzybski’s 1947 memoir—not a small task in itself. Charlotte did what she could to help him and at the end of October, she wrote to fill him in on some important information she thought he should have for the biography:

Probably you have been reading about the many books recently published on ‘The Life of Chopin’. If you do not get the Sunday New York Times, I call your attention to the Book Review Section of October 16th. I mention this because of your interest in Alfred’s biography. I also wonder if you are acquainted with the publication, Poland of Today,...The issue of October 1949 is dedicated to the Centenary of Chopin’s Death. Alfred believes it is a socio-culturally important issue and would also be helpful in understanding the Poland of seventy years ago, into which Alfred was born. We do not have any extra copies, or we would be glad to send you one. (54)

Korzybski had his own backlog of correspondence, also the Manhood Introduction to finish, and in October a new project that fell into his lap—an invitation to speak at a psychology symposium at the University of Texas in Austin. He couldn’t refuse. The psychology department there had gotten a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to conduct an ongoing symposium on “Perception: A Focus for Personality Analysis”. Speakers would individually lecture in Texas from October 1949 until June 1950, each presenting a different aspect of the topic, which would constitute their contribution to a published book of the proceedings [Perception: An Approach to Personality]. Beforehand, they would each get a theoretical outline of the symposium by the organizers, Professors Robert R. Blake and Glenn V. Ramsey, who presented the first paper on “Perceptual Processes as Basic to an Understanding of Complex Behavior”. Each speaker would also get summaries of the preceding speakers’ presentations and would have the opportunity to revise their contribution for the book after all invited papers had been presented. Those invited included a number of significant and rising figures in the behavioral sciences. (One of the contributors, James G. Miller had only recently suggested “behavioral sciences” as a general integrating term for the life and social sciences). Besides Miller, the invited speakers included: Clifford T. Morgan, Frank A. Beach, Ernest R. Hilgard, Jerome S. Bruner, Wayne Dennis, Urie Brofenbrenner, Norman Cameron, Carl R. Rogers, George S. Klein, and Else Frenkel-Brunswik. Korzybski—the only non-academically connected, non-psychologist/non-psychiatrist in the bunch—was to give his presentation in the last week of January (the date later moved to early April). He would get an honorarium and travel expenses for the trip to Texas for both him and Charlotte. By means of his applied epistemological approach, Korzybski could probably have said something useful about any area related to “functional determinants of perceptual processes”, but his specific assignment focused on ‘the effect on perceptual processes of the language system”. He considered the invitation a great privilege and his contribution something worth sweating over. On the way back from Texas, he planned to stop in Chicago, where the GS group there wanted him to speak and he could also visit Mira. He would write his contribution, with Charlotte’s help, mainly over the first two months of 1950. But now as the end of the year approached, along with the annual Holiday Intensive, he wanted to see if he could get further along, even done, with the Introduction to Manhood. This meant another trip to New York City in November.

By this time, Mira had gotten fairly hobbled and pretty much housebound. She didn’t feel stable walking alone outside and needed help in the apartment as well. The young woman who had lived with her had left some time before. Mira wrote to Alfred about a 24-year- old medical student, Albert William Kneller, who had just started staying in the spare bedroom where Charlotte usually slept during visits. In exchange for the room and a small stipend, “Dr. Bill”—as Mira called him—was helping her with cooking, cleaning and other chores and would accompany her on those increasingly rare times when she left the apartment. Alfred, of course, felt concerned but with the help she received from her doctors, neighbors, etc., and now Dr. Bill, Mira still seemed to manage.

And despite her problems she seemed to maintain a positive outlook. She continued to write to Alfred often—little notes with memories of their earlier times together, references to his work, and interesting things she heard on the radio or read about. For instance, she had found this reference to time-binding in a collection of essays, Reflections On Our Age, newly published by UNESCO: Julian Huxley’s essay “A Re-definition of Progress”, referred to “the present culmination of life in the emergence of man—the microcosm, the time-binders with brain and mind capable of annihilating the sequence of events and tying them together in the unity of consciousness;...” As Mira noted, there was no direct reference to Alfred or his work.(55) Mira’s stream of references, suggestions, links, and leads both great and small had continued to exert an influence on the content of Alfred’s formulating. And if in his general mood he also seemed more mellow, perhaps even more hopeful—in spite of all the messes and problems he continued to observe or personally had to deal with—perhaps a little bit of Mira’s somewhat sunnier disposition had also gradually rubbed off on him. But she probably wasn’t trying to give him a subliminal message when she sent him a volume called Sunspots in Action, which she thought he might like to read. He telegrammed her on Thursday, November 17 (56):

Thanks Your Letters. Grateful For Sunspots. Am Going To New York Friday To Work On Manhood. Will Be At Thirty-Three West Fifty-First Street, As Before, Love Alfred

Within a few days he and Charlotte were back at Hotel 33. Sometimes he just sat in his room alone, silently contemplating, visualizing what he still had left to say in the Manhood Introduction. Then he would talk things out with Charlotte, wrestling to get what he wanted into words; then having finally gotten something written, both of them would delouse it; and then the whole process would begin again. Over the past two years, as they had worked on the Introduction, Korzybski no doubt spent a fair amount of time contemplating the arc of his life’s work from its beginnings to the present. He sought to express that in the Introduction. The delay in getting it finished probably inspired frustration, but he knew the writing and editing process had to take its course. Earlier in the spring, also at Hotel 33, as he and Charlotte had worked away, he had jokingly said as she took notes, “This new introduction by Korzybski has been edited by me, as it was not finished.”(57) He surely intended this as a joke and not a prediction. Until the piece seemed good enough for publishing, he and Charlotte would have to push on with steady work. He wanted to get it done. So this extended period away from the distractions of Lime Rock seemed necessary. They stayed in New York for four and a half weeks.

Throughout this period, Charlotte kept Mira filled in on their progress. And as he sometimes did, Alfred would pencil-in short notes to Mira at the end of Charlotte’s letters. Just as Mira had pushed Alfred to write the book in the first place, she had ‘nagged’ him for years about the importance of time-binding when he had placed it to the side. Mira’s impetus had helped him to get re-engaged with the notion, and there was no one more eager than her to see the Second Edition in print once again.

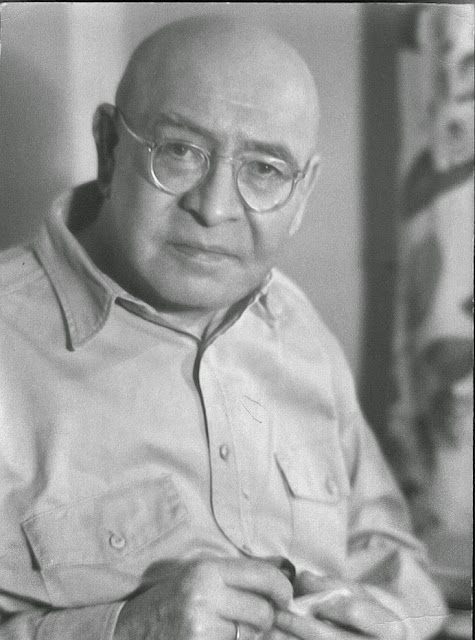

A little more than two weeks into their stay, Charlotte wrote to her that Alfred had caught another ‘bug’, a chest cold, but otherwise he felt alright and was working hard. As Charlotte told her, the Introduction had a good structure in spite of that eternal—or infernal—delousing. They felt very anxious to have it done. Other than Alfred inviting 25 people up to their rooms for a December 7 cocktail party for Charlotte’s birthday, they didn’t appear to socialize or go out much. One visitor, Dr. Wolf, a student of Alfred’s from the last summer seminar, came socially but also examined Alfred and prescribed some quinine, which seemed to help his cold. Wolf also told them about a friend of his, photographer Lotte Jacobi, who had photographed many writers, artists, and scientists in Weimer Germany and, as a Jew, had escaped to the U.S. before World War II and was now living in New York. She was interested in Alfred’s work and wanted to take his picture. Alfred didn’t object, Charlotte contacted her, and Lotte Jacobi came to Hotel 33 sometime during the next few weeks to do so.

|

| Alfred Korzybski, December 1949 (Photographed by Lotte Jacobi) |

Dear ____

As this half-century draws to a close, I want to share with you our hopes for the years to come. I wish that our whole ‘semantic family’ could toast together the New Year, and the New Era...(58)In the seminar group photograph he looked rather worn and tired. He, Kendig, and Charlotte could all use a good rest. That wasn’t going to happen. As a compromise perhaps, as soon as they had gotten back from New York, he had Charlotte write to Mr. McKee from the GS group in Chicago to cancel the lecture he was supposed to give there. It’s quite likely that also at his impetus, his University of Texas presentation got moved back from the end of January to April 3. The Intensive was over on January 3. He had several more days for personal interviews with students, and then he and Charlotte had to get rolling on the paper for the Texas conference. The Texas paper would put Manhood on the back burner for now.

With Mira’s birthday on January 16, and her and Alfred’s 31st wedding anniversary on January 17, 1950, a flurry of congratulatory telegrams and notes in the mail went back and forth for several days between Chicago and Lime Rock. The Institute staff drank with Alfred to Mira’s birthday and their anniversary. Mira and Dr. Bill toasted to her and Alfred on glasses of orange juice. Alfred sent a handwritten note to Mira (59):

January 17,1950Dearest,

Pardon pencil but I want a carbon copy. Many thanks for your notes and wire. We had a very warm ‘burstday party’ and anniversary for you. Yes, our union has perhaps had a world influence, thanks to you. Without you I certainly would never attempt my work. In my two books, as you know I give full credit to you and am so happy that I can provide for your life security.

Charlotte and I are sweating over the paper for Texas, certainly she did the main ‘sweating’ and did really a splendid work, you will have a copy. Otherwise no news except that damn sweating day and night, which is no news.

With my Devoted best wishes Donk

Notes

You may download a pdf of all of the book's reference notes (including a note on primary source material and abbreviations used) from the link labeled Notes on the Contents page. The pdf of the Bibliography, linked on the Contents page contains full information on referenced books and articles.

54. Charlotte Schuchardt to Ken Keyes, Jr., 10/25/1949. IGS Archives.

55. MEK to AK, 10/7/1949. AK Archives, Box 22, Folder 1.

56. AK to MEK, 11/17/1949. AK Archives, Box 22, Folder 1.

57. Charlotte Schuchardt, “Editor’s Note” to Second Edition of Manhood of Humanity, p. v.

58. AK “1950 New Years Party Invitation”, 12/22/1949. IGS Archives.

No comments:

Post a Comment